In middle school I took a class called, “How to Get There.” Our assignment was to plan all of the logistics for an annual two-week field trip. We were eager, awkward 11 year olds who couldn’t wait to go on an adventure but first needed to learn how to prepare. My heart raced the first time I had to dial the phone and speak to an adult stranger about hotel reservations. But I found my groove when it came to the food. I loved menu planning, making shopping lists, and even figuring out how and where to store it all in the back of the school van. The experience sparked a life-long interest in understanding how things really work behind the scenes and turned out to be a perfect prerequisite for owning a food supply chain business. Fast forward 45+ years, and my days at Firsthand Foods are filled with figuring out how to get meat from farm to market.

Food supply chains are showing up in the news like they have never been before, at least in my lifetime. The pandemic has brought supply chains front and center as we try to understand why we can’t find or buy all the foods we’re accustomed to. Where’s the cereal I usually buy? Why can’t I get my favorite brand of yogurt? How come you’re always out of chicken? We’re learning that long, complex supply chains are less resilient in the face of disasters like pandemics and extreme weather events. The ability to pivot in the face of disruption is a strong argument for building a decentralized food system with shorter, more localized supply chains. It is one reason among many. One way to think about the benefits of localized food chains is to consider who is actually benefiting. For example:

Better for Farmers

Short, local supply chains provide farmers with better market access and more independence. Markets served by long globalized supply chains are difficult for farmers to penetrate on their own, severely hampering their negotiating power and offering an ever shrinking percentage of the consumer dollar. A recent feature on the The Daily podcast illustrates how right now beef cattle producers are actually losing money despite rising beef costs at the grocery store. Guess who’s experiencing rising profits? The four global companies who control the meat market. Both farmers and consumers lose in this scenario.

Contrast that with the 35 farmers in our local supply chain who are “price makers.” They get a say in what we pay them and are able to negotiate the terms of our engagement. Just last month our pork producers came to us with a price increase necessitated by rising costs for fertilizer, fuel, and feed. They did so reluctantly, not wanting the price increase to depress sales. On the other hand, if they don’t pass along those costs, they risk losing their farms— and that’s the last thing any of us want. In our model, farmers hold on to their independence and dignity, all while earning between 36 and 65 percent of the revenues (depending on the species) we generate.

Better for Consumers

Short, local supply chains, though admittedly not always the most efficient or least costly, offer many other benefits that consumers value, including safety, security, and freshness. Consider a pound of ground beef that might contain meat from 1,000 different animals or the California-grown microgreens that are all washed in the same sink. The longer and more complicated the supply chain, the more things can go wrong. In our model, each pack of ground beef or sausage we sell comes from an individual animal (or small batch of animals) and can be traced back to a specific farm, processor, and processing date. If we had an E.Coli or Salmonella outbreak (fingers crossed this never happens), the problem could be identified and contained within hours and its impact would be felt only on a small scale. Contrast this with the potential population-level impact if and when something goes wrong with vertically integrated silo-like supply chains.

One reason chefs love our products is their freshness. They taste the difference. Our fresh cuts of beef, pork, and lamb are delivered to customers just two to three days after processing. Our ground products are frozen immediately after processing to minimize water loss and retain flavor. This is relatively easy to achieve given the short distance between our farmers, processing partners and warehouse.

Better for Communities

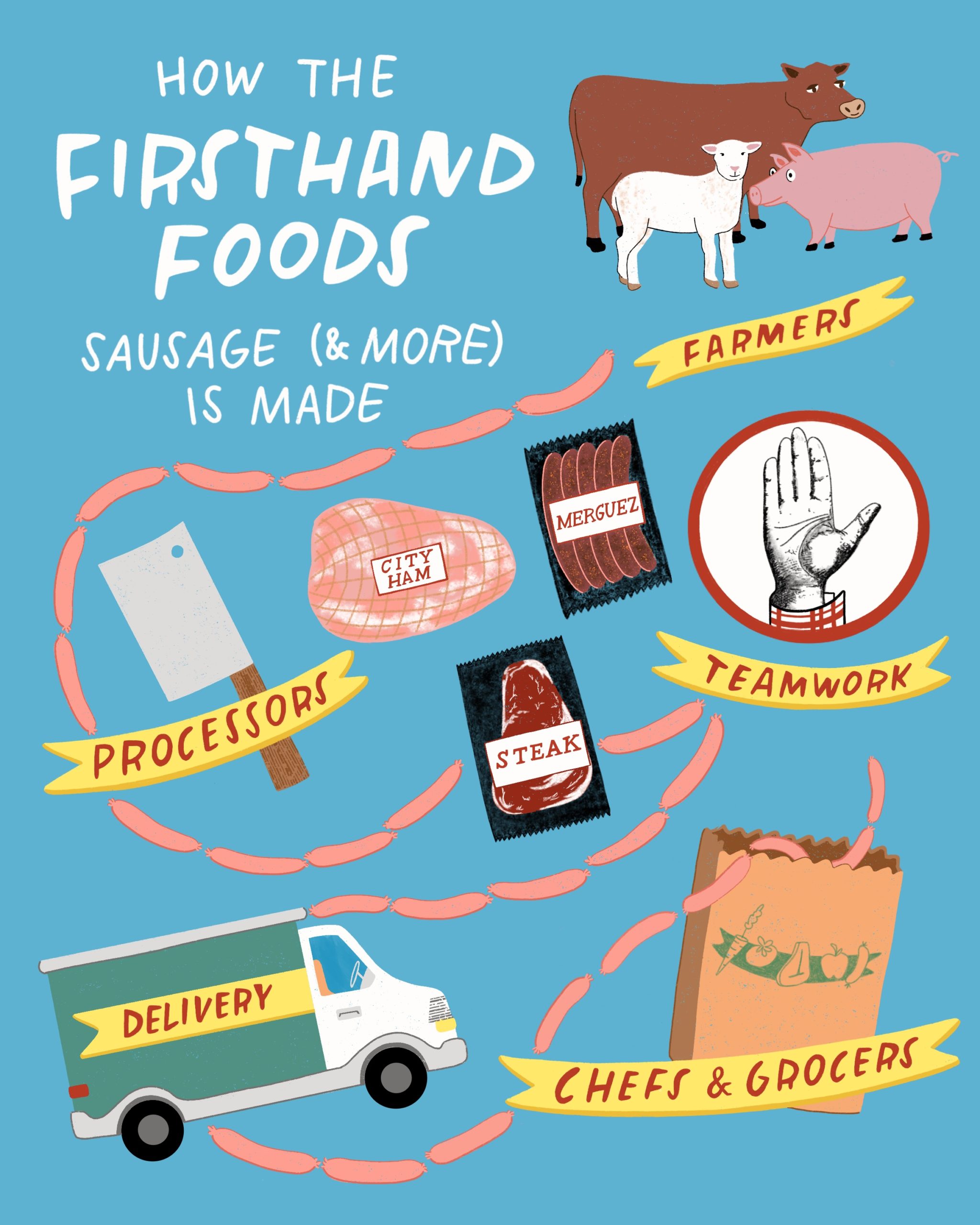

Short, local supply chains have the advantage of helping to reinvest in and strengthen our communities. As a food hub, Firsthand Foods is an intermediary that brings local farmers together with local consumers. We operate within a 500 mile region that extends north from Durham as far as Washington, DC and southwest as far as Greenville, South Carolina. Our supply chain partners include 35 small-scale livestock producers, four family-run meat processing businesses, two local transportation businesses, and approximately 100 regular wholesale restaurant, retail, and institutional customers.

More than 75 percent of the revenues we bring in every year are distributed to our supply chain partners. Right now that means approximately $1.5M per year is going back out to the local farmers and processors in our network, money they spend on farm supplies, food, household goods, taxes, and more. Contrast this with long, global supply chains where most of the money from communities is extracted and the profits end up enriching just a few distant companies with no local ties.

We aim to help build a decentralized, regional food system that diversifies the sources of our food and strengthens our local food system so that we are less reliant on food trucked in from far away. Where we see similar efforts underway across the country, we look for ways to work together and share knowledge.

Better for the Environment

Long, global supply chains have been built around the principle of efficiency while ignoring environmental and social impacts. This focus on efficiency has led us to develop a food system that exploits land and labor. Yes, we have “cheap” food, but at what cost and for how long before the system can no longer sustain itself? While every state in our nation produces food, the vast majority of it is actually grown in either California or the midwest. We are overly-reliant on just two regions of the country for our food and both are facing serious environmental challenges including drought, wildfires, and ground and surface water contamination.

There are many potential environmental benefits to growing and distributing food closer to home. One is fewer food miles traveled and thus lower GHG emissions (although this can’t be assumed and must be designed for). Another is waste reduction, as shorter supply chains offer more opportunities for food reuse, nutrient recycling, and less packaging. There is no question that transitioning to shorter, local supply chains would require changes in consumer buying habits to align with seasonal availability. Less produce from California, if not replaced by locally grown substitutes, could have real public health impacts given the important role of fresh fruits and vegetables in a healthy diet.

We need to start having conversations about where our food comes from and considering the trade-offs of moving to a more resilient food system. At the end of the day, real food security comes at least in part from knowing and trusting the people who are growing and raising our food. So, what lessons would we teach in a “How We Get There” class about sustainable food chains? We get there by building trust and interdependence within a network of decentralized supply chains that benefit entire communities, including consumers and farmers.